WORDS BYSuprabha Seshan

ARTWORK BYDipitha Dilipan

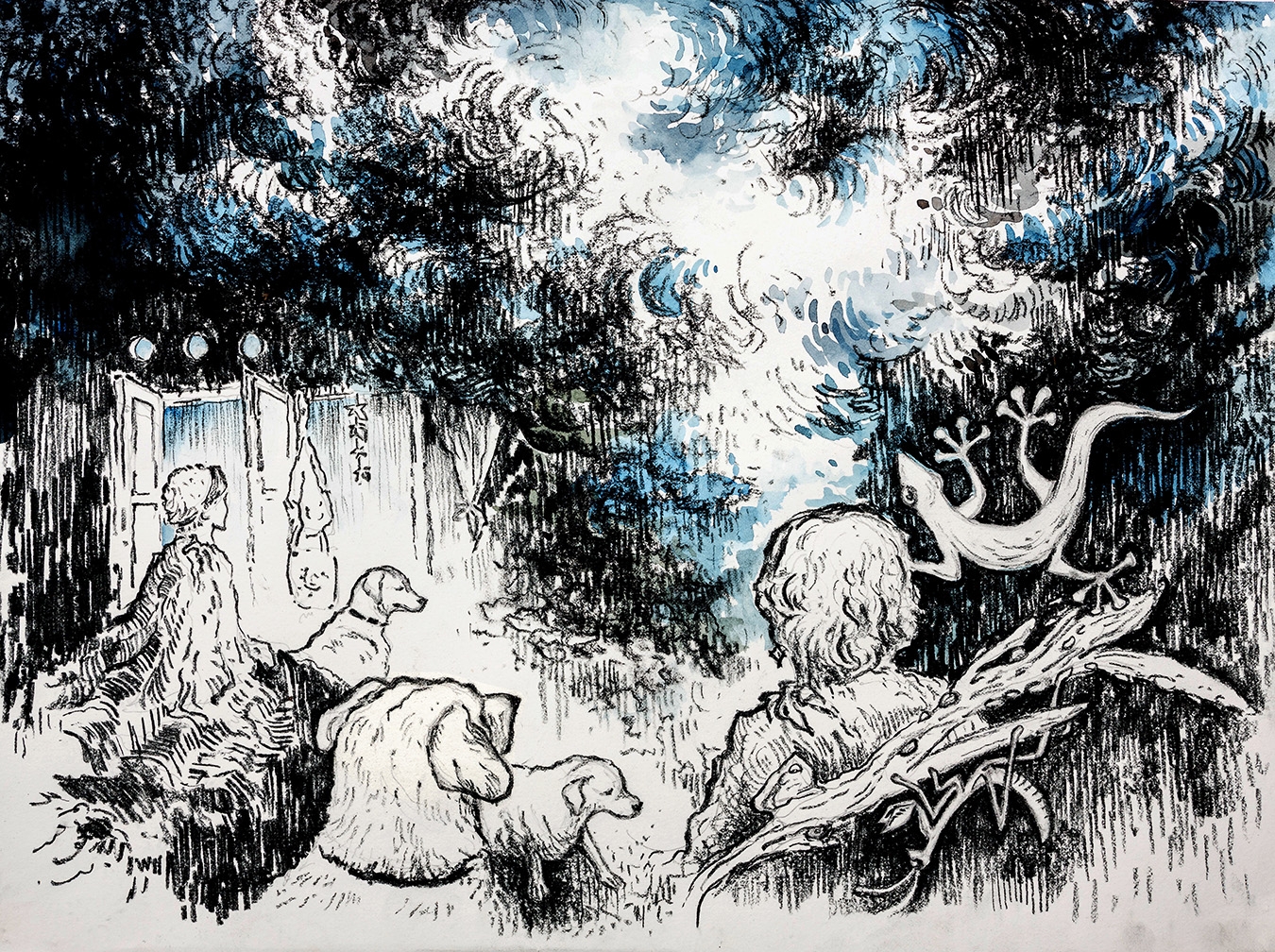

A savage night storms the hills of Wayanad, soaking my room in pitch-black. Half-awake, roused from dreamtime by a cool, whistling draught, I blink into the darkest moment of the year. The village street lamps are down. There’s been a power outage for days. Traffic’s stalled by roads falling apart, streams running amok. Giant trees downed like matchsticks. Slopes collapsing into slurry. I’m inside the mother of all downpours. Sodden awareness rushes into my lungs. The ocean is here. Lightning thoughts shoot from an underworld of confusion, alarm, and sleep. A sky ocean. I’m on tenuous crust sloshing in the sheer swell of the monsoon—a wind system born of continental deep time. In the Keralan month of Karkidakam.

Voice of thunder. Brutal passage of wild waters.

Is there anything else?

This rain, this seething crush of rain, with its immense weight and power, pounds the cantilevered roof of the Eyrie—my roost on the third floor of a lone building on a ridge. Searing flash. Low, rushing clouds. Split-second conjuration of whipping trees and roiling hills. A white pigeon in the rafters. She’s been sheltering for a few days through the deluge, keeping to the rain-shadow side of the ridge-top dwelling. Suddenly, she’s there, resting in our eaves, dropping piles of pigeon shit on wooden railings, spooking the dogs with her just-out-of-reach calm.

There are others who make this communal home: writhing caterpillar multitudes shedding hairy moults. Slender potter wasps sticking tiny terracotta domes onto window frames. Generations of solitary crab spiders hunting silently underfoot at night. Pipistrelle bat clans clicking in and out of the twilight. Mottled forest cockroaches shuffling in lintels. Jerusalem crickets clutching bathroom towels with spiny forearms. Endless streams of multi-tasking ant hordes scurrying through biscuits and cupboards, carrying their eggs and larvae; nesting in my clothing.

All of us subject to the same storm.

I check on my mother. She’s sleeping on the far side of the glass-walled room, insensible to the blitzkrieg weather. She’s removed her hearing aids and pulled her woollen headband over her eyes. With the next flash, I spot the dogs curled up around my low bed: Puck to my left, Bonnie to my right, Sushi at my feet. Three geckos stud the ceiling.

Stretching both arms, I splay my fingers. Now I see you, now I don’t. The distance from cloud base to forest canopy on the Periya ridge, a kilometre away, is zero. I’d noted this earlier during the day. Now, in the strobe-lit night, I know it’s zero here too. I’m in the cloud, or just below. Sheet lightning dances around. Incandescent clarity between blackouts, no greys. From the tiles at the edge of the roof, glittering cables of rainwater lash us to the ocean.

In this tumult between blacker-than-black and whiter-than-white, on a steep ridge curling around swampy valleys thrashing with rainforest trees, on the rim of a slender mountain range rippling off an ancient craton—we renew ourselves.

Mother, dogs, pigeon, caterpillars, wasps, spiders, bats, cricket, ants (their eggs and larvae). The million-beinged forest, with its rivulets, swamps, buttressed trees. Elephants, martens, humans, snakes, earthworms, pill millipedes. Ferns, mosses, algae, fungi. The pullulating majority.

And me.

Who doesn’t break tonight will surely strengthen.

I’m galvanized by the cloudburst, but apprehensive. Will the roof rip? Might the lightning conductor snap? Can the glass window panes hold out? Sturdy as this structure is, with steel-woven pillars and foundations resting on grown ground, its courtyard gets waterlogged in hard, continuous rain. Every year, we dig a drain to release the ankle-deep water that accumulates on saturated soil. Tonight, an upwelling fear that parts of the courtyard, and the hill, could slide into the valley, like one did in Kodagu some years ago— taking with it a house belonging to a friend of a friend. A beautiful house barrelled into the valley by stormwater, one of many devastating landslides that have become commonplace in recent years. Shocking slippages down mountain slopes; liquefied earth; boulders and trees pelting down what once seemed to be unassailable escarpments.

Countless homes pulverised like this. Homes of humans and non-humans. And countless homes, born from this. Obliterated and reborn.

Rainforest flaying. Billowing, crashing. Gutted and reeling. Clouds detonating. Every monsoon. Every Karkidakam. I feel the crackling surge in my blood and bones; in every cell and nerve of my body.

The atavistic renewal erases all refuge: the blackness will swallow me. Elemental nature will take my body—itself a concord of elements. I glimpse my whitened hands in the pounding discotheque of a storm. Fingers, palms, wrists, knuckles, mounds of Venus, life lines—all may go tonight.

I place them on my slow-moving belly, warm from sleep, rising and falling to its own rhythm—its muscled drummer within. There is no greater comfort than this: hands to skin, palms to stomach, left thumb to sternum, right to navel. Cross the ribs, up the outer arms to the shoulders. Grasp the bony girdle. Pull. Release. Set the forefinger in the jugular notch; check the pulse.

Despite changes, the skin remains sensitive, my most infallible mode of perception. No guessing. No distance. No taxonomies. Just a rippling spread of minute sensations— orchestrating into a fulsome knowing, subliminal, alive. This delicious organ—and with it the organism, a wildling fostered for over 300 moons by this forest—will go.

Fingers of attention travel up my neck, the side of my face, to my hair. The maelstrom will devour every strand. Each hair follicle, scalp tissue and facial muscle; each pad of cartilage of my nose and roll of flesh around eyes, cheek, mouth, and chin. Each bone—the generations of lived experience: affection, wisdom, hubris, folly ossified—will crumble into the darkness. My father’s heart. His mother’s nose. The nerve body passed down through the maternal line. The senses and juices—blood, tears, snot, saliva, urine, sweat—all cues and flows through this animal body; spoor of self and others mingling, transformed within. A tasting of cells, by cells. Interoception. And through the hands, the whole body—its behaviour, ecology and energies—unfolds. A wondrous terrain. Haptic knowing.

Connect. Attend. Move. Shift from the one touching to the one being touched. Merge. Back to the spine, toes, small of the back, neck, shoulder blades. Travel the one you know. The one you are.

A forest within this membrane. An ecology of feelings. A hydrosphere of fluids. Galaxies of pulsations. Now citronella-tinted—the trace of forest walks, keeping leeches out of clothes and body.

And from this palpable, breathing unity, spill forth—through the T-shirt and the sleeping bag, into the dark. The primordium. Expand. Into the forest, the hills and valleys; wind, rain, night. Where do you end—and where does everyone else begin?

Such are the thoughts and tendernesses—words and attunements—flitting during inclement weather. I’ve long sensed that the monsoon on this edge of Wayanad is the true heart of darkness. Its roaring syncopations drench the windward slopes of these steep mountains, carrying them down, slope by slope, every Karkidakam, the peak rain month between mid-July and mid-August. A wind choreographed annually from even more ancient trade winds blasts an up-tilted plateau—the Deccan. Hardened lava flows weathered over billions of years, rimmed by peaks, riven by waters. Once molten, then diamantine, this gargantuan rock crumbles towards the ocean, season by season

A violent thrumming in every cell of every living being. Now the abyss. Now the brink. Now the squalling silence.

At 92, my mother learns the ways of the monsoon in Wayanad. She moved in with me during the pandemic. I couldn’t travel up and down from Bangalore, 300 kilometres away; the restrictions made my choices unbearable. I had a forest to care for, and a mother. Both ancient and child-like. Both alone, and not alone. Eternally wise, yet heartbreakingly vulnerable. Powerful and wilful. Capricious with age. My mentors. My nurturers. Increasingly, my wards. To avoid travelling, I brought my biological mother to the Eyrie. Three years have sped by, and my life no longer feels divided. I am exactly where I most wish to be. There is an unspoken truth: I have always loved you, and will love you always. No more up and down between forest and city. No more internal conflict in choosing between my two mothers. A familial existence finally—everyone I care for most unconditionally, within walking distance.

It’s where you dwell that your care most glows.

The storm hammers on. I have no sense of time. So black. My guess is we’re still within deep night—astronomical night, when the sun lies eighteen degrees below the horizon. The fury will die before dawn. I refuse to look at clocks at night, tuning instead to a circadian rhythm untethered from devices.

Puck whines. He wants to go out. His faint, feathery under-tail is a beacon to the door. Unsure of what I see, I use other cues. I match the whine, the angle, imagine the little dog’s outline, and suddenly I see the tail. Look away, it disappears. Look long with soft eyes, it appears. Eyeless fish in subterranean caves grow whole taxonomies of darkness without sunlight. I may have to as well, weak as my retinas are now. Minimising lamps and torches after sundown helps to entrain a feeling for the night—a practice I’ve long kept before losing sight in one eye.

Lightning is now sporadic. My vision still wrestles with the shift from tungsten-white to pitch-black. The right eye does little more than receive light. Its wad-of-gel altered by weakness and injury—registers a grey quivering blur, still perceiving but undiscerning. Only in absolute darkness do both eyes converse, align and reach their deeper quiet. If not the mind, the body readies for its final tumble into oblivion.

I open the northern door to the Eyrie. Fibreglass barricades the verandah for monsoon months; it’s soaking wet. The buffeting sheets let rain in but block the wind’s full force. Often I feel raptor-like: the high, wide view, the rushing in and out; scarves and ponchos fluttering. Tonight, I’m defenceless, prey to the storm spirits. My powerful wings, soaked to the bone, would fail me if I ventured out.

Puck baulks—and comes back in. I shut the door and move to the window, my eagle-self, watching the flashing, writhing land battered by wind from the heaving seas. Later, when it dies down, I will glide over canopy and swoop through trees, as I do over my mind. Sometimes the inner world is as feathered as the outer. As ripe and rife with beauty and hubris. Snatch a scurrying thought, or an errant motive; snag a zombified threat from the men with the super machines. Carry them off like limp rodents in my talons, drop them off cliffs in the western horizon: how else to stop the advancing things?

Back to the low hard bed, feet feeling their way. For a year now, I’ve slept on a thin razai over a Tibetan carpet rolled on a plank supported by four short pillar-sections salvaged from leftover woodwork. Six inches off the floor is where I dream best. I pull on the old goose-down sleeping bag—a veteran of many journeys since my youth— and retrieve notebook and pen from the side table. Before sleep, I open to a blank page and leave it ready for writing in the dark, for noting down images and phrases without rising. My fingers find the top of the page. I scribble. The page is paler than the night, but I can’t see the words. I will decipher the muse by day.

Water moves, changes form, but remains constant. If not within you, it is under you, around you, or above you. Mammalian eyes create the perception of inner and outer realms. I feel the rocking of my mind when deeply resting. I feel the fluid supporting my fascia. In and out are mental devices; the tissues of these lungs, and of this body, know otherwise—that there can be no damming of this water. There has never been more water, nor less, through geologic time. The rumbling belly of the monsoon is a good time to remember this. Mind flooded by the primacy of torrential rain. A counterpoint keening. Who am I if not this play of elements? And who are these, if not I?

30,000 litres of various fluids have left my body to soak this land. My lungs have circulated and drenched 120 million litres of air. By 2024, 32 years of vital flows into and out of this ridge; itself pushed around by the molten splurge of the mantle through layers of crust beneath the oceans.

Now this land, now the currents, now these trees, now the rain; soon the moon and stars and sun, the whole turning sky. Have I not reached the ocean many times over, circled the planet, and returned as the great monsoon winds and the life-giving rain that replenishes this organic continuum—a rain already vivified by the forest’s creatures and trees? More pertinent to my associative mind, hell-bent on its own enquiry, have I not reached the city many times, only to return, as city, with sludge and toxic effluents in every gust of my body?

Have my two mothers merged? Are they but one? Biological Ma, ecological Amme.

Mala Amme, Kaattu Amme, Karkidaka Thaaye!

Follow the dots, they say, and then stop.

The logic excludes their own bodies, and also the machines.

They: the toters of supremacist logic, self-proclaimed deus ex machina. The abrupt evolutionary appearance of artifacted ingenuity, followed by weapons, monies, symbols, monumental structures and exclusionary hierarchies. Civilisation.

For me, it is simpler: a continuous case of habeas corpus, filed every moment. Every attempt to remove me from here only deepens resolve. I hear the writ in the tempest. To remove the wind from the wind, or the rain from the rain, will be the tragic coda of the human song.

Any attempt to remove me from this—my home in the monsoon—or to sever mind from body; or this brown, bipedal, warm-blooded being from its vibrant forest ensemble, is the clarion call to redress civilisation’s wrong.

A blanket of silence slowly descends. Water-drop frogs start up in the canopy, slow rising rattles meeting pulse in the temple, tic-tic-tic, easy, light, musical. I dissolve into the darkness. Time disappears, as does the storm.

Just as another dream begins, a tingle. Bladder, lower belly. Drop by drop, a pressure; soon a swelling, the sluice gate firming. The insistence is non-negotiable. I have to go. Sudden overwhelming sleep keeps my limbs heavy. The pencil slides off the page. The book drops to the side. I curl up. Eyes shut. Mind descends into a deeper cavern. A delicious, annoying sensation prevents the final surrender. Why are the most ordinary of body actions the most delightful and also contrary?

Sushi flaps her ears. My mother clears her throat. I get up. Feet on terracotta tiles, I skirt the edge of the wooden stairway to the attic, step over invisible black Bonnie, make my way to the pale pot gleaming, half-dream my relief into the pee, and pee noisily into the stillness.

I return to bed. It’s still dark, but the slightest tinge of grey appears on the eastern horizon. I lie on my back.

Again, skin; hello. Miraculous being. Shoulders, neck, ribs and belly. Down the thighs, backs of knees, ankles, to feet. Witness enters the toes; slight itch, even a burn; memory of saltwater soothing the rot-infused, leech-pierced sole. Witness roams back along the tailbone and spine, pauses on the flaring nostrils, pulls in squall-drenched air. Tastes it. On to the back of the throat, gracing the palate, tip of tongue tasting gums and teeth. A tingling of the epiglottis syncs me with my mother clearing her throat. I walk across and pat her curled small back. Empathy and its opposite seem to both live through the skin, for me.

Sushi’s ear flapping grows more vigorous. She sits up, head tilted, left ear down. Getting up suddenly, she comes to me for comfort. I stroke her ears gently. She groans.

A recollection slips in; last evening’s call with KT, a former ship captain. I had a longing to hear tales of the savage sea at night. His laconic, gravelly voice evoked a terrifying scene—blackness, water, a crew aboard a pitching vessel. He recommended The Wager, by David Grann. I tell him about the forest in the churning Karkidakam night. We know the exhilaration; we know the helplessness. Our mutual love of the natural world carries the sea in his voice and the monsoonal forest in mine.

The gale powers up again. I hear the canopy lashing. Trees unquelled. I imagine mosses drenched but feistier. Spores of fungi and ferns racing with the currents. Pollen and seeds of plants. Those who make the rain and summon winds from the sea—who cool the air and contain all storms.

I think of the animals. Hiding, huddling, perching, shivering. Flailing, swimming. Drowning.

I learned cross-border tactics in interspecies life, love, and war in Wayanad, Kerala— much of this in the clash between the oldest continuous culture on the land surface of the planet, the rainforest, and the youngest: a toxic version of humanoid excess, modern industrial civilisation.

Old Mother Forest has been my supreme commandant, the Queen of Queens. At a conservative estimate, she has endured for 100 million years. I’m in her thrall. Wise and wicked. Beautiful and deadly. She cares—and she cackles. Her Buddha heart and demon senses trick one to live radically, defying limitation.

For years, she swaddled me. All along she bled me, bit me, skinned me. She charged every cell in my body with potions, pricks, infusions. Old Mother Forest. Mala Amme, Mala. She can turn anything into a flower or leaf, a tendril or thorn, a critter or swarm. She can deploy the ultimate seed bomb. She can take a girl and turn her into a hag, leeching her dry, transmuting her blood to blossoms.

Her leafy, glittering, sun-flecked eyes bewitch the universe.

They bewitch me.

The Periya imam calls—human breath through seasonal breath. Long, sustained vowels carried in 100% aerial humidity. I peer out. No lights in the village yet. The faintest silhouettes of books against clouds and trees. Black-bottomed monsoon clouds sail swiftly. Eyes droop. The storm yields to serenity; it spreads through my body, merges with the air, the dogs, and my mother, and courses through the land.

Crick in the neck; head on pillow by window. I'd dozed deeply. Swift and sweet had been the descent into the dreamworld after a night hurled by cataclysmic winds. Restless Puck seems to have slept too. He’s always first up. The weather gets to him sometimes. I rely on him as an alarm. We’re both crepuscular creatures. Bonnie and Sushi snore.

Waving a torch, Ma gets up. Moving slowly, tentatively, she looks for slippers; reaches for her walker. She’s tough. From her, even at this age, I learn a particular intelligence, the perspicacious language of intuition; she knows me better than I do myself.

I’m soon wide awake. The transition from sleep to wakefulness is pivotal. I love that defining moment - the bewildering contrast to the Mesmer of the dream realm; inter-fused states and realities. I dreamt of a deluge within a dream. Over the years, I've lost the

boundary between sleep and waking consciousness. Now I’m a curious traveler between worlds conjured by unfathomable entities. I defend the right to dream. My favourite daily moment, the gloaming, marking the intro and outro of sleep; flesh-bound creatureliness merging with the cosmos; individuating with light and disappearing into darkness.I stretch, make my bed, sit on the pot, stand at the sink, change into day gear: T-shirt and loose pants, overlay of printed cotton, half-kimono shirt. Murali and Siddu are also up. They cross paths in the saddle area between ridges, one off to sleep, the other just risen. Security shifts. Tonight, it is they who need protection.

A few frogs call. Four, five, many? One species or two? I want to rename the water-drop frog, castanet frog. Name-games can counter name-games in taxonomy and natural history. In anything—human lore, branding, science, love—how you name or nickname depends on the cosiness of your relationship.

The hills and valleys here have many names. As do the plants and animals.

So does the rain.

The land is uncannily still. Not a leaf moves. Was the storm a dream? Was the dream a storm? The Eyrie, my cloud-pummelled perch—my haven—settles at last; yielding me to peace and shimmering green.

***